Black-boxes, Consciousness, and the Octopus

“If we want to understand other minds, the minds of cephalopods are the most other of all.

Other Minds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life

Confidence Spectrum: 80%

I

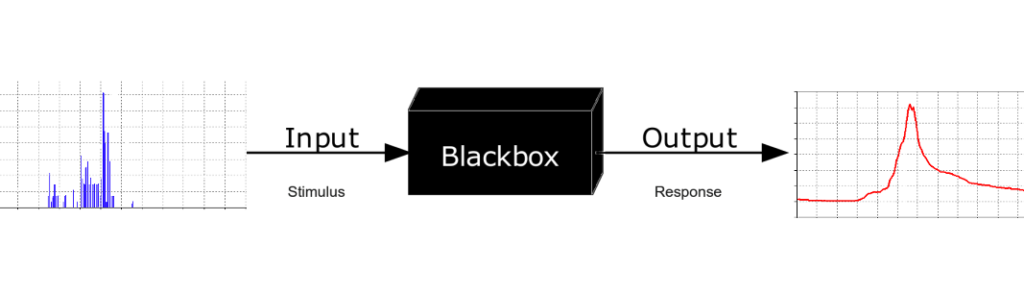

The 'psych' fields (psychology, psychiatry, psychotherapy, etc.) are currently stuck using a black-box model of consciousness, human behavior, and theory of mind. Black-box models figure out how a system works by only looking at its inputs and outputs. Everything in the middle (i.e. the black box) isn't understood but doesn't have to be understood to produce relatively strong predictions in the outputs.

At first glance, this makes the psych fields seem less 'science-y' or unreliable. Do they know what they are doing?? And while it's true that we should not confuse progress made while using a black-box model with a deep understanding of the subject, the use of black-box models is more common than you'd think - especially for complex topics.

An example: you can reliably tap certain areas of your phone in a certain order (inputs) and -viola- your phone acts as a navigation assistant (outputs). Exactly what happens between the inputs and outputs (transistors, heat sensors, aerospace radio wave physics, computational algorithms, etc.) is a black box to you. But that's okay - you don't need to know those things to use your phone as a GPS! 99% of the time, things work according to plan. When they don't there are people who understand this particular black-box and can fix things when our [finger tapping] ---> [personal navigation assistant] model isn't working correctly.

But there are some things, 'consciousness', theory of mind, etc., for which we use a black-box model, and nobody fully understands what happens in the box. What do we do to troubleshoot these things? How do we begin to figure out what is going on inside of these black-boxes?

We use edge cases!

Edge cases have helped us poke and prod at the nature of human consciousness for a long time. Phineus Gage is an example commonly talked about in high school. People with Dissociative Personality Disorder push the boundary of what a person is. Feral children have taught us a lot about developmental psychology. 'Entity' encounters during psychedelic use is a common cross-cultural phenomenon. Lucid dreaming exists. And split-brain experiments done by scientist Roger Sperry in the 1980's resulted in a Nobel Prize in Medicine.

"[Each hemisphere is] indeed a conscious system in its own right, perceiving, thinking, remembering, reasoning, willing, and emoting, all at a characteristically human level, and ... both the left and the right hemisphere may be conscious simultaneously in different, even in mutually conflicting, mental experiences that run along in parallel"

— Roger Wolcott Sperry, 1974

The list of edge cases that have given insights into the inner workings of our black-box is too long to list. But there is one, in particular, that started around 530 million years ago deep in the ocean. Namely, the emergence of cephalopods.

II

Insert Peter Godfrey-Smith's book: Other Minds. It explores the origins of consciousness and intelligent life by looking at Cephalopods. Cephalopods are an alien-looking group of marine invertebrates who have little to no hard body parts. Squids, octopuses, and cuttlefish are examples. Of all the cephalopods, octopuses, in particular, are surprisingly intelligent and display signs of self-awareness and consciousness. Their intelligence is not 'human-like'; give it an elementary school math exam, and it will try to eat the pen. But if we judge them in their environment by their ability to model the world, adapt, react, plan, and navigate uncertainty... they do pretty well. They build homes out of sunken objects, use tools, respond to social cues, etc. Octopuses in captivity have even been known to sneak into adjacent aquariums for late-night snacks. Individuals have personalities. All of these behaviors (including many more explored in the book) make some cephalopods seem to be self-aware.

Other animals are intelligent (and potentially conscious) too though. Dogs, birds, monkeys, etc. However, octopuses are an edge case because they aren't vertebrates. They evolutionarily branched off from us vertebrates long before consciousness, self-awareness, or intelligence was around. Our last common ancestor with them is a primitive worm from 600 million years ago. Why is that important? This suggests that consciousness has independently arisen more than once. So when you trace back our ancestors looking for the first time the lights of consciousness flickered on, there are two answers. One from our lineage, one from theirs.

Evolution's windy road has led to large integrated nervous systems that produce self-awareness (atleast!) twice. How many other times has it emerged? How common is it? Perhaps the ingredients for consciousness aren't as rare as we thought.

III

I'll give you that Octopuses can seem smart, but are they conscious?

Until we have a measured, operational definition of how consciousness arises and what the ethereal term really is, one can't say for certain. But with that logic, you really can't say with much certainty that anyone is conscious except yourself. How can you be sure everyone around you isn't a philosophical zombie? In the meantime, we can make some educated conjectures as to what is required for consciousness and what forms of life meet those requirements.

What would the requirements for consciousness be? One likely candidate is that consciousness is a by-product of creating an internal model of the world. If we're modeling 'out there' we've inadvertently created an 'in here'. Simply reacting to a stimulus isn't enough. A worm can react to a stimulus and a tree grow toward sunlight without an internal representation of the world. But by creating an internal representation and coincidently creating a distinction between self and other, a canvas for consciousness is created. Octopuses appear to have such a canvas.

Now, the experience of being an octopus is likely different from what your everyday experience is like. Octopuses paint the canvas of consciousness with different colors and shapes than humans do. To see this more clearly, consider how an infant experiences the world. An infant has no object permanence, an underdeveloped memory, no internal dialogue because they haven't developed a language yet, literally can't comprehend disjunctive syllogisms, etc. The experience of being an infant is fundamentally different than that of an adult. The experience of being an octopus is no different. Depending on the features available (attention span, memory, sensorium, complex pattern recognition, etc.) a unique picture is painted on the canvas of consciousness that shapes what its experience is like. We can idolize our 'version' and try to reserve the word conscious for a 'human-like' experience, but that is a word game. It seems there are plenty of other forms of experience painted on the canvas of consciousness that are different than the one you occupy now. Likely, you will go through more than one of these throughout your life whether due to age or drug use (and yes, alcohol is a drug). Similarly, octopuses have a consciousness that is distinctive from ours but conscious none-the-less.

So cephalopods, like the octopus, give us a clue about the inside of consciousness's black-box because they appear to be an example of consciousness arising a second time in the tree of life, independent of our vertebrate lineage. As fascinating as this is, the black-box of consciousness is still largely unilluminated. We don't have an answer to the Hard Problem - that is, why does a subjective experience arise in the first place? Can't world modeling, cognition, etc. all be done 'in the dark'? I think we'll get closer to that answer as we find more instances of consciousness emergence like in our octopus tree-of-life cousins. As we do so, we'll better map the landscape of the 'types' of consciousness. And maybe eventually we'll stumble across a type of consciousness that is not from an independent branch of our tree-of-life, but from an entirely independent tree.