This is a brain dump about Section Three of Hofstadter’s collection of essays - Metamagical Themas. For an introduction to the book and hyperlinks to all the sections, see HERE. Moving forward, I may end up splitting up future sections into a part 1 and part 2 because this is a long post that probably deters you from finishing it despite some of my favorite ideas being found towards the end.

Patterns

You’ve probably seen faces where they don’t really exist - such as when looking at an electrical outlet. This is called Pareidolia. Fundamentally, this is all the brain does - detect patterns. It is really good at this, and most of the pattern matching happens on subtle, subconscious levels. So much so, that what is perceived is not Reality. Instead, raw sensory data has been warped and bent to fit into the patterns the mind is expecting. This is not just the case with ‘high complexity’ skills like face detection. It seems to be pattern detection all the way down.

Complex vision is just an increasingly complicated combination of ‘edge’ detectors1.

Furthermore, neurobiological theories of psychosis seem to converge into an understanding of hallucinations and paranoia as abnormal predictive processing.2 I.e., abnormal pattern detection.

Further furthermore, the work I’ve read in the science of consciousness argues that consciousness emerges from a self-referential perception-action loop that works via pattern-matching prediction models.3

Dr. Eagleman - a neuroscientist from Stanford - unveiled a wearable tech-device in his 2015 TED talk that gives the user a ‘pulse’ on Twitter, the stock market, or whatever other data source you want to pick up on patterns from. The real insight with this device, to me, is that the brain is an all-purpose pattern-detecting monster. Data in, patterns out. One can hi-jack the brain’s propensity for pattern detection by transforming data from non-sensory kinds (stock market prices, trade volume, etc.) into sensory kinds (pulsatile vibration onto the back, burst vibrations on the shoulder, etc.).

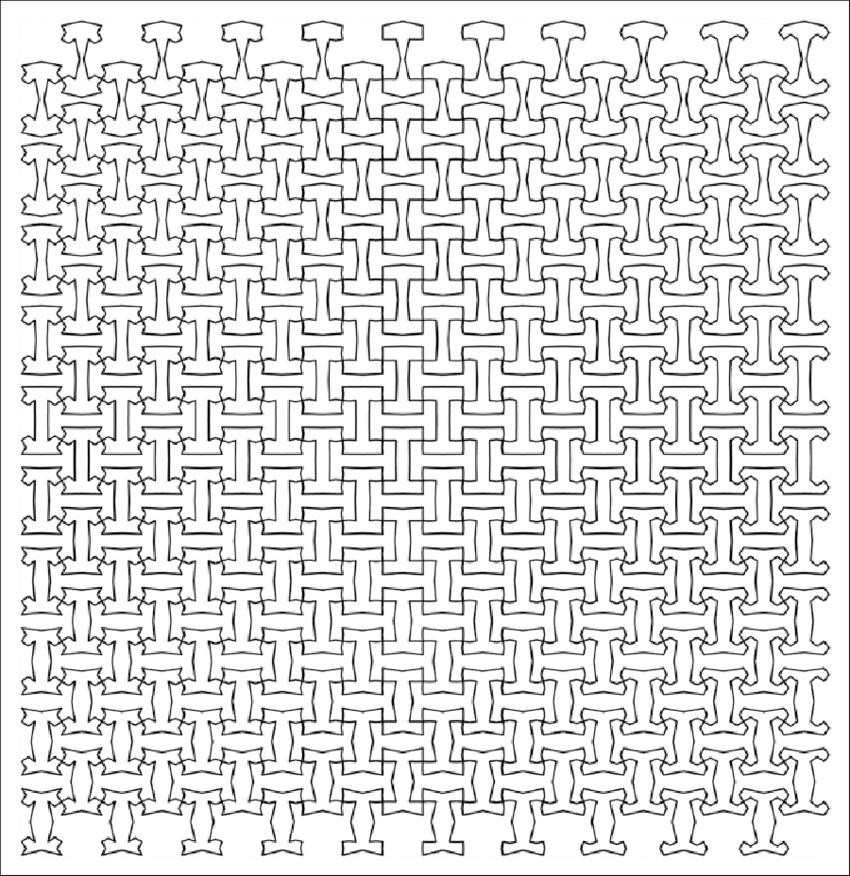

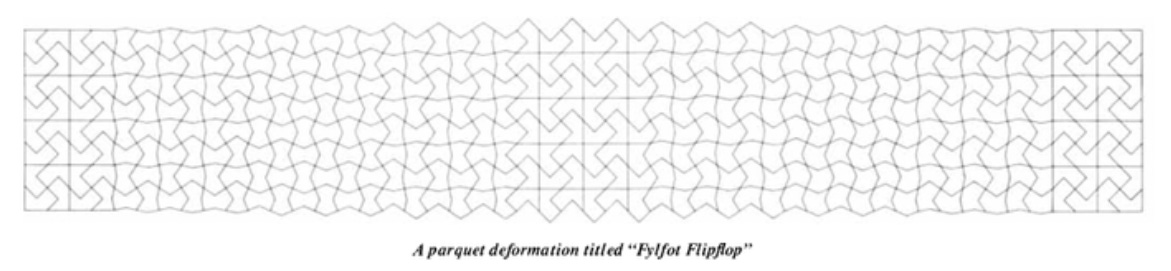

So patterns and their detection seem to be an important theme behind what it means to be human. In a very Hofstader way, Hofstader does not lay out such a direct argument. Instead, he dances around the subject, exploring the concept of creativity from a bunch of different angles. He starts his exploration of creativity with Parquet deformations. Parquet deformations are mosaics with some sort of transition snuck in. When done well, one side of the mosaic is drastically different than the other, but there’s no clear phase transition.

Looking at lots of patterns and tesselations like those above (he has over a dozen in his essay collection) led Hofstader to wonder: How does creativity work? Is there an overlying architecture to creativity? Not an algorithm that would make simple variants of a given design. That isn’t how human minds work (and thus, for argument's sake, not how human creativity works).4 Humans, Hofstader would argue, look at something (a cup), abstract from it some quality that they observe in the creation itself (cups have to be held), and fiddle with that quality (what if a cup had handles (i.e., a mug) or had a holding part that went beneath the liquid part (i.e., a wine glass stem)). Note, this newly abstracted quality may never have been thought of explicitly by the inventor of the original item (i.e., the classic cup), but it is in the eye of the beholder nonetheless. Hofstader calls these ethereal aspects of a concept that can be fiddled with, thus creatively played with, knobs. We will talk about knobs a lot later on, but first, we need to clarify something. When is doing something a creative act, and when is it bullshit?

On Nonsense

There is a realm that straddles the line between what is sensible and what is bullshit. Hofstader calls this the realm of Nonsense.

Nonsense is not simply the antonym of sensibility in this particular usage of the word. Let’s circle back to patterns for a minute.

As we go about the world, we learn by slowly building up mental models of how things are supposed to work. We learn, not through a deep understanding of physics and math, but by noticing patterns. We notice that gravity pulls things back down to earth, balls tend to arch in a certain way, etc. I would argue we also pick up on cultural norms and learn language in the same way - through unconscious pattern detection. Nonsense is when we come across something that sort of fits those models of the world, but in other ways, violates them. An example:

There was an old man of St. Bees

Who was stung in the arm by a wasp.

When asked, "Does it hurt?"

He replied, "No, it doesn't —

I'm so glad it wasn't a hornet."

This is a limerick by W. S. Gilbert that I’d consider Nonsense. You expect a limerick to rhyme, have a punch line, etc. This limerick above tickles those expectations, but doesn’t fully meet them. It doesn't rhyme but is close enough to be frustrated at the lack thereof. Its meter is bumpy. It kind of sets up a story and ends with confidence as if the final line wrapped the limerick up- but of course, it hasn’t. It sets off my pattern detection buzzers just enough to get pattern-matched into ‘I’m a Limerick’, but then proceeds to fail all the requirements. When I go back and read it again, it still gets pattern-matched as a Limerick, but still fails to meet the requirements! What Nonsense!

Did W.S. Gilbert have all of this in his head when writing the limerick? I have no idea, but I think it is irrelevant. It tickled my concept of limerick just enough. Nonsense is in the eye of the beholder. It would be reasonable to read the limerick and simply conclude it is ‘dumb’ and not witty nonsense. That’s what I think when I see John Mccracaken’s modern art masterpiece- Red Plank.

Red Plank (with riveting sequels like ‘black plank’) is a plank that leans against a wall. That’s it. Red Plank is valued at ~ $500,000. I had the luxury(?) of seeing red plank in person once while it was on tour. I can promise you; it is that underwhelming.

Here’s some art commentary on the work.

Untitled (Red Plank) stands at just over 6’8”, just the right height to be within the human scale without being personified into an abstract human figure. The colors and titles of the works are also unique; McCracken often intuits such decisions while he executes the work, reinforcing the mysterious self-possession of the planks. While he sometimes gives them names of shapes or ideas they evoke, the title of the present work is explicitly minimal, stating only what it is: a red plank…

Striking in their monolithic simplicity and characterized by pure, monochromatic surfaces, McCracken’s handcrafted “planks,” which rest on the floor and lean against the wall, successfully blur the boundary between painting and sculpture.Striking in their monolithic simplicity and characterized by pure, monochromatic surfaces, McCracken’s handcrafted “planks,” which rest on the floor and lean against the wall, successfully blur the boundary between painting and sculpture…. he strove to make objects that were also “hallucinatory” or “other-wordly.” From 1966 forward McCracken’s signature form was the vividly monochrome “plank,” of which Red Plank is a prime example—stately, monolithic, yet leaning casually against the gallery wall.These sleek sculptures exist “between two worlds,” the artist explained, “the floor representing the physical world of standing objects, trees, cars, buildings, human bodies … and the wall representing the world of the imagination, illusionist painting space, [and] human mental space.”

To me, this has crossed over from nonsense to bullshit. There is no tickling of my expectations, but whoever wrote these art commentaries probably feels differently. To each their own. The point is, it is a fine line, and a subjective one, that separates the meaningful from the meaningless. One person’s nonsense is another one’s bullshit (and another one’s sensible).

Limericks and Red Planks are not life-changing, but when we find Nonsense that straddles the border just right, it can be. Nonsense can be used to intentionally push and probe at the concept boundaries you didn’t realize were there. Zen Buddhism is known for its cryptic koans. Their purpose is to help you notice what was right in front of you the whole time but were blind to. It’s bullshit until it’s not. I still don’t know what the sound of one hand clapping is, but if it’s anything like emptying my cup, I hope to find out.

Knobs

Earlier, I brought up the concept of ‘cupness’. But ‘cupness’ is kind of vague. There is a cup of water next to me now at my desk. But in my head, is a subconscious blueprint for ‘cupness’ that contains much more nuance than a single cup can. In a discussion of creativity, this distinction between an object and the mind's concept of the object is crucial. Why? Because concepts have knobs. The blueprint for ‘cupness’ might include knobs like ‘height > width’, ‘holds liquids’, ‘used when thirsty’, ‘has handle’, ‘stored next to plates’, etc.

These knobs are at the core of creativity. We can intentionally turn them.

Imagine that one summer evening you and Ann Yone5 have just walked into a surprisingly crowded coffeehouse.

Now go ahead and manufacture few variants on that scene, in whatever ways you want. What kinds of things do you come up with when you deliberately "slip" this scene into hypothetical variants of itself?

Before reading on, ACTUALLY DO THIS EXERCISE ↑

If you're like most people, you'll come up with some pretty obvious slippages, made by moving along what seem to be the most obvious "axes of slippability". Typical examples are:

I could have come with Eve Rybody instead of Ann Yone.

We could have gone to a pancake house instead of a coffeehouse.

The coffeehouse could have been nearly empty instead of full.

It could have been a winter's evening instead of a summer's

These are examples of intentional knob-turning. Hofstader (and likely you) came up with some of the scenario’s most obvious knobs, but one could have changed a near-infinite number of other ‘knobs’ on this scene (see the pizza example below). Where creativity lies, I would argue, is in the ability to naturally recognize all these other knobs.

This begs the question: How can you see knobs that you don’t see?

Slippage.

To spark new ideas, we can pay attention when slippage occurs. Knobs reveal themselves when we accidentally have concepts slip between each other. For example, what is going on when someone accidentally says ‘February’ instead of ‘Tuesday’? I would argue, it is unveiling a conceptual knob. Namely that they both are part of an ordered list, and both come second in that list. Because of that link, the concepts bled into each other. This word mismatch is more reasonable than mixing up ‘Zebra’ instead of ‘Tuesday’ - there’s no shared knob between those! An unintentional mix-up of that nature sounds pathological.

Now that we know this knob exists by examining an accidental slippage, we can combine other concepts that have ‘ordered’ lists and make something creative. We could write a book about the topic. Perhaps it would be titled: Belium, Beburary, and Buesday.6

The fluidity of concepts provided by dreams and drugs is culturally noteworthy for providing inspiration and deep insights. When LSD helped Watson Crick unravel the structure of DNA, it wasn’t because it made Crick ‘more intelligent’. It made his concepts slippery. Overall, it would seem that slippage is a feature, not a bug7. Careful observation of slippages can provide a chance to probe into the murk of our unconscious conceptual networks. Something that Freud and psychoanalysis popularized. The accuracy of such probing is suspect and not to be taken as Truth, but Freudian slips do point at something. Concepts are slippery, and the way they slip is not random.

Slippage of thought is a remarkably invisible phenomenon, given its ubiquity. People simply don't recognize how curiously selective they are in their "choice" of what is and what is not a hingepoint in how they think of an event. It all seems so natural as to require no explanation.

I dropped a slice of pizza on the floor of a pizza place the other evening.

My friend Don, who was less hungry than I was, immediately sympathized, saying, "Too bad I didn't drop one of my pieces-or that you didn't drop one of mine instead of one of yours." Sounds sensible. But why didn't he say, "Too bad the pizza isn't larger"? His choice revealed that to his unconscious mind, it seemed sensible to switch the role-filler in a given event, as if to imply that a pizza-slice-droppage had been in the cards for that evening, that God had flipped a coin and, unluckily for me, it had come out with me as the dropper instead of Don-but that it could have come out the other way around.

Some hypothetical replacement scenarios-I like to call them "subjunctive instant replays"-are compelling, and come to mind by reflex. They are not idle musings but very natural human emotional responses to a common type of occurrence. Other subjunctive instant replays have little intuitive appeal and seem far-fetched, although it is hard to say just why. Consider the following list:

Too bad they didn't give us a replacement piece.

Lucky we weren't in a really fancy restaurant.

Too bad gravity isn't weaker, so that you could have caught it before it hit the ground.

Lucky it wasn't a beaker filled with poison.

Too bad it wasn't a fork.

Lucky it wasn't a piece of good china.

Too bad eating off floors isn't hygienic.

Lucky you didn't drop the whole pizza.

Too bad it wasn't the people at the next table who dropped their pizza.

Lucky there was no carpet in here.

Too bad you were the hungry one, rather than me.

Going through these you probably thought - that's weird. Or that doesn't even make sense. This is revealing the knobs of the concept that you had in your head - and remember the hard part is noticing the knobs in the first place! It's interesting what knobs people see or don't see. When applied to personal situations - it can reveal subtleties of the person's psychology.

Consider the following: A man walks into a bustling coffeehouse and says, "I'm sure glad I'm not a waitress here tonight!". He could’ve instead said, "If I were the owner here, I'd hire more staff" or “This sucks. I can’t believe it is this busy on my one day off”. Each of these expressions reveals something about the person making the remark and the innate knobs they naturally grasp at.

More Hofstader (emphasis mine):

Another quick example: I was having a conversation with someone who told me he came from Whiting, Indiana. Since I didn't know where that was, he explained, "Whiting is very near Chicago-in fact, it would be in Illinois if it weren't for the state line." Like the earlier one, this remark was dropped casually; it was certainly not an effort to be witty. He didn't chuckle, nor did I. I simply flashed a quick smile, signaling my understanding of his meaning, and then we went on. But try to analyze what this remark means! On a logical level, it is somewhat like a tautology. Of course Whiting would be in Illinois if the Illinois state line made it be so-but if that's all he meant, it is an empty remark, because it holds just as well for cities thousands of miles from Chicago. But clearly, the notion he had in mind was that there is an accidental quality to where boundary lines fall, a notion that there are counterfactual worlds "close" to ours, worlds in which the Illinois-Indiana line had gotten placed a couple of miles further east, and so on. And his remark tacitly assumed that he and I shared such intuitions about the impermanence and arbitrariness of geographical boundary lines, intuitions about how state lines could "slip".

Remarks like this betray the hidden "fault lines of the mind"; they show which things are solid and which things can slip. And yet, they also reveal that nothing is reliably unslippable. Context contributes an unexpected quality to the knobs that are perceived on a given concept. The knobs are not displayed in a nice, neat little control panel, forevermore unchangeable.

Instead, changing the context is like taking a tour around the concept, and as you get to see it from various angles, more and more of its knobs are revealed. Some people get to be good at perceiving fresh new knobs on concepts where others thought there were none.

It’s important to realize that knobs are not static, unchanging things permanently attached to concepts waiting to be discovered. Just as a concept changes from person to person (See figure 2 from here), so do their knobs.

A colleague in my medical school class majored in French Studies while taking medical training prereqs in undergrad. At first, this may seem like a waste of time. But in the world of knobs, it is anything but. It helps provide a new perspective and, with it, a new series of knobs that others may not have seen.

TLDR

Concepts have knobs. Creativity is the identification and manipulation of these knobs. This is very much a human act. Unconsciously, concepts slip and spark new ideas. This unconscious slippage can also reveal your internal conceptual mapping in ways active thinking fails to do.

Typographical Niches

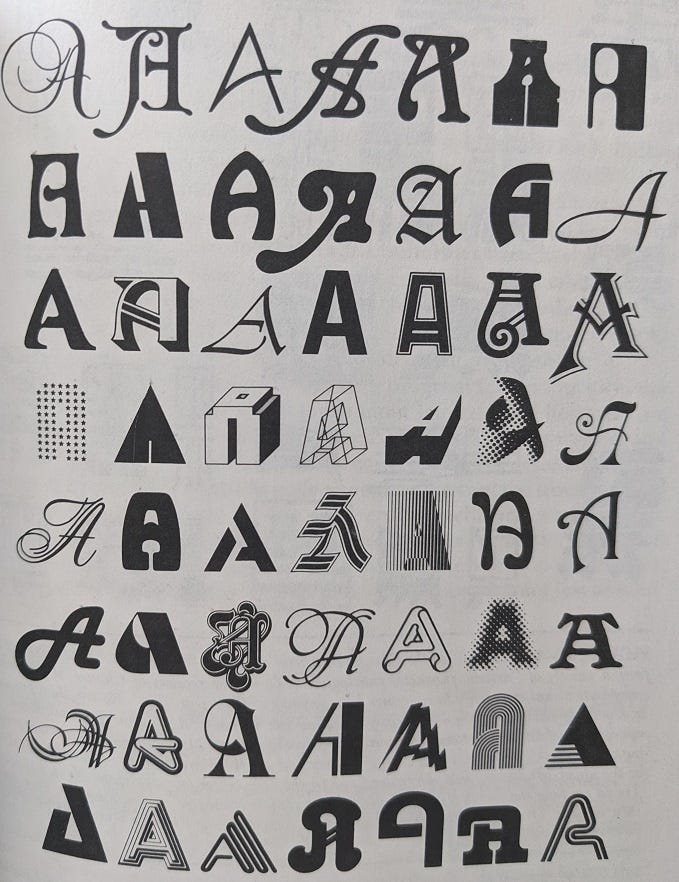

To conclude, I’m going to try to summarize what Hofstader spends 40 pages on: detailing what the ‘spirit’ of the letter is. In other words, how do we determine an ‘a’ is an ‘a’ when there are so many variations of the way it is drawn? How is it so intuitive to read a font that you have never seen before? Identifying the ‘spirit’ of ‘a’ is an exercise in intentionally trying to identify the knobs within a given concept space.

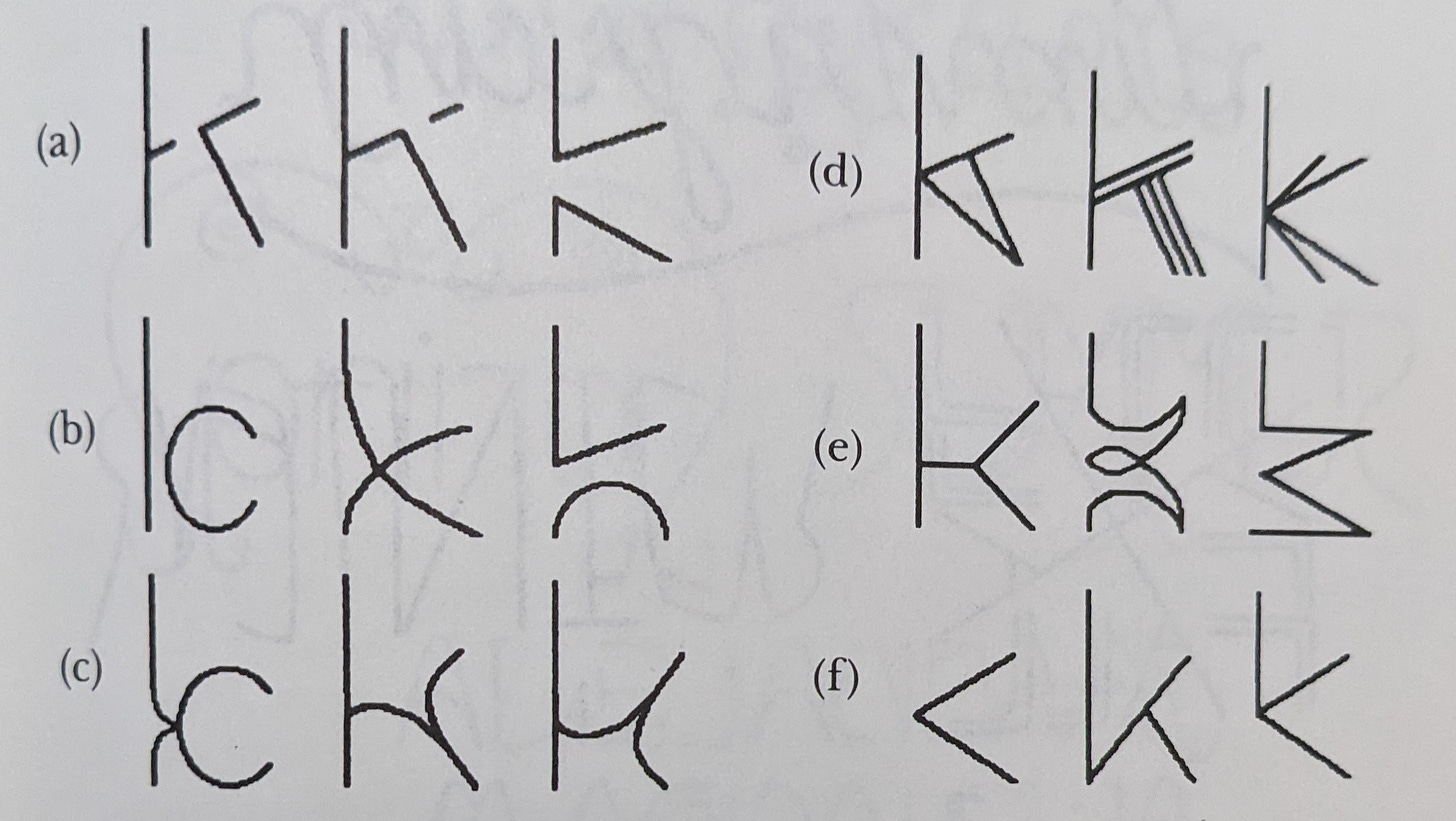

Hofstader argues, that the spirit of a letter isn’t retained in what the total letter looks like. It is found in what fundamental modular ‘roles’ its strokes fulfill. For example, ‘b’ has a ‘post role’ on the left, a ‘bowl role’ on the bottom right. ‘k’ has a similar left-sided ‘post role’ but an open-facing ‘right role’. When the role criteria of a letter are met, the mind detects the ‘spirit’ of the letter.

An interesting thing to notice is the essence of a letter is all or none. There is no ‘kinda b’ essence. Even when there is evidence of more than one letter, such as in ‘h’ and ‘k’ below, the mind’s eye will choose one or the other.

The pattern-detecting mind is not happy with something resembling two things at once. It can switch back and forth quickly, but like the duck-rabbit illusion, we can only see one essence at a time. It is as if the spirit of a given letter exists in a conceptual landscape made of valleys and ridges. The valleys are the typographical niches. Switching between KEN and HEN is an act of switching valleys; there is no in-between because there is no stability along the ridges. It is remarkable how instantaneously things get pattern-matched into these valleys. Below is the letter A in a bunch of fonts. They vary a lot, but without even the energy of thought, they are all recognizable.

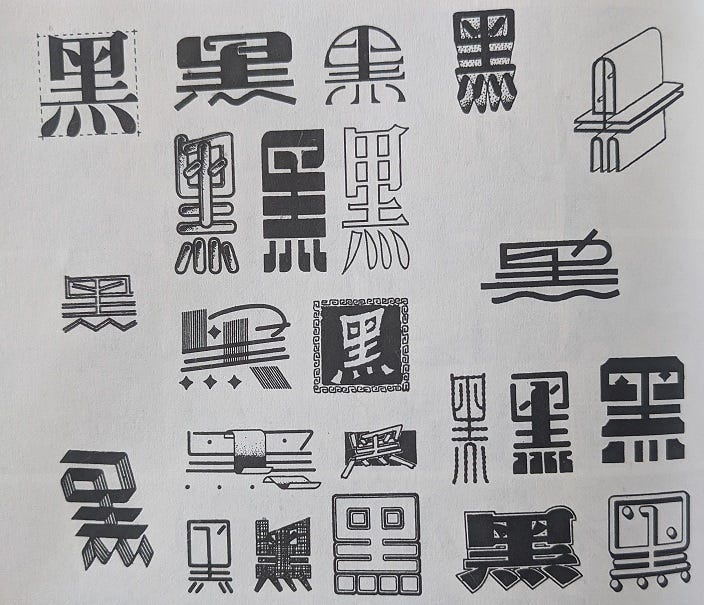

Compare this to the same exercise with a Chinese character below.

It’s not clear they are all the same character. You can maybe put effort into it and find similarities. You could convince yourself they are all the same ‘spirit’. But that process feels a lot different. What if I told you one of the Chinese caligraphies was actually a different letter? Which one would it be? Now what if I revealed they are actually 3 different characters - can you find the three patterns? Could you ever tell without knowledge of the all the other Chinese character’s shapes/modular roles (i.e. their ‘spirits’)? As we mentioned when starting off this post, perception is not raw sensory information; it is the result of making raw sensory data fit into the patterns that you were already expecting.

Condensing everything from above, it becomes apparent that the essence of a letter has (at least) 2 components. First, there can be a near-infinite amount of variation on a letter as long as the modular ‘roles’ are fulfilled. Squiggles and twirls are fine - just make sure it retains the necessary modular roles. Second, the spirit of any given letter is dictated not just by the letter itself, but also by the existence of other letters. For example, ‘T’ very quickly becomes ‘t’ as soon as any vertical line is present above its crossbar. The Chinese character is difficult to pattern-match, in part, because you don’t know what other characters exist to help shape it.

This principle - that the spirit of something is shaped by the other spirits in the same idea-space - seems like it could be applied more broadly.

Edge detectors work by recognizing when a change occurs. I.e., when a pattern stops.

Here I’m referring to the work of people like Anil Seth, who wrote Being You (which I’ve read), and Andy Clark who wrote The Experience Machine and Surfing Uncertainty (which I tried to read, but it was too difficult. Thankfully, we have bloggers to help us out)

I imagine a ‘computer’ will be able to do this eventually. By computer, I mean a man-made thing but a man-made thing that probably won’t operate on classic programming like we use now. It will be something with a recursive nature that takes in information, updates, acts - but at that point it is beginning to sound a lot like the self-referential prediction-error minimizing human mind.

At first, I changed the celebrity names he uses because I had never heard of them, and this was written 40 years ago. Upon looking them up, I realized he was referring to ‘anyone’ and ‘everybody’. I now notice that my expectation of names referring to actual individuals was incorrect. A new knob was (re)discovered!

Would Celium, Cuesday, and Cebruary be too much Nonsense?

Comparatively, we wouldn’t want our computer code to ‘slip’ with its code.