Pruning

An Underrated Life Skill

I once came across a paper in Nature Communications that gave the following question:

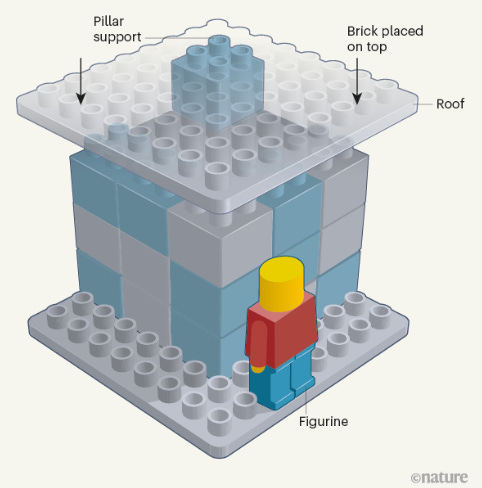

Consider the Lego structure depicted in Figure 1, in which a figurine is placed under a roof supported by a single pillar at one corner. How would you change this structure so that you could put a masonry brick on top of it without crushing the figurine, bearing in mind that each additional block added costs 10 cents?

Most people suggested adding another Lego piece to the three remaining corners so the heavy brick would have its weight equally distributed. But there’s a more straightforward answer - remove the pesky Lego piece in the back corner that makes the roof all wonky. This is ‘free’ and involves fewer pieces overall.

When I first read the solution, I was unimpressed. My immediate reaction was, ‘Duh, I didn't know I could do that. I thought I had to add a piece.’

However, it slowly dawned on me - that's the point. The argument the Nature paper makes is that there is a deep human bias towards addition when problem-solving. They aren't saying it's super hard to counteract this bias or that some genius-level understanding of things will be revealed if you do so. Their claim is simple: as a human, you tend to add instead of subtract.

Solving problems in terms of subtraction (which moving forward, I will call sometimes call pruning) is a simple, easy, and often more effective way to solve a problem. Let’s look at some examples.

I

Problem: My social media feed isn't as interesting as it used to be.

The number of accounts one follows has a natural tendency to grow over time. When our feed isn't giving us enough dopamine, there is an explore tab to find new accounts; but no ‘help-me-prune’ tab exists. This design choice exacerbates the human bias of addition. When we feel unsatisfied with our feed, we add more to it, hoping to improve it. But the solution isn't to chronically dilute your feed; it's to prune down the list you currently follow.

Hot take: A half-assed decision to follow an account shouldn’t have years of consequences. Unfollow ~ 50% of the accounts you follow right now on Twitter, Instagram, etc. It is a hard pill to swallow. I know people think they need to keep following accounts A, B, and C for that off chance they post something relevant. But the accounts you truly will miss will return to you serendipitously. They will be retweeted or forwarded to you. Better yet, you might actively recognize their absence. When that happens, make the conscious decision to follow them again. If you don’t remember them, how memorable were they?

Life is too short to have a diluted feed. Prune it.

II

Problem: My <medical condition> needs addressed.

There is a tendency in healthcare to add medications in order to solve problems. Every doctor wisely nods when they hear the adage ‘less is more.’ But in practice, that goes out the window.1 High blood pressure? Let's add a blood pressure medication to your regimen. God forbid we work on subtracting causative factors like salty personal diets, food desserts, SES, lack of exercise, etc.

Psychiatry is particularly guilty. Still depressed and anxious while on buspirone, sertraline, mirtazapine, and duloxetine? Maybe we need to add adjunctive aripiprazole!

No, we don’t need to do that.

But when someone asks for help in the confines of a rushed office visit, there is a deep human bias telling us to add something to fix the problem...and stuff like this happens.

Often, medicines don’t solve problems. They ‘reduce symptoms on average in large population studies.’

Primum non nocere - First do no harm. Think before you add.2

III

Problem: I can't afford the things I want.

The obvious solution to this problem is to make more money. As you can guess from the post's theme, maybe there's another way.

Have you considered pruning elsewhere? It's harder to do this if you don't have a budget, but spending less might be easier than earning more.

Most digital businesses offer subscriptions instead of products. It sucks. You pay X dollars a month for Y months and end up forking out X*Y. Two years later, you still don’t own anything.

My subscription list includes apps like Readwise and Waking Up. Thankfully, I haven't yet been kicked off my family’s Netflix and Spotify accounts. Google tricked me into saving all the photos of my daughter on the cloud so that when I ran out of space, I’d start paying $2 a month. God forbid you support small passion projects like Psychiatry at the Margins. It all adds up. I’m jealous of my friend who has a Nuts.com subscription. I’m partially addicted to productivity apps, and Motion, among many others, is tempting. I've slowly been kicked off my family’s Adobe which switched from a digital product to a digital subscription a few years ago. Does my limited photo editing warrant a subscription? I have a Fitbit watch, but it teases me with features since I don’t pay for ‘premium.’ My wife has a Grammerly subscription, and it's surprisingly good. As a family, we started using You Need A Budget (YNAB) - which is yet another subscription. Hell, my toilet paper comes as a subscription. The list of things to subscribe to is endless.

Like social media, subscriptions need a purge every six months or so. You will quickly come back to the ones that matter.

My only concern here is that it disfavors supporting small individual creators. I’ve always wished the government would give every citizen 15 dollars a month that can only be used to support personal creative projects. Like this blog, someone’s Twitch channel, etc. You could cap how much someone can earn from this money in a year as an incentive to spread the wealth and minimize fraud. So much creativity and community building could be fostered this way. There are a lot of people on the internet; getting 100 people to give $5 a month adds up to a lot of coffee.

IV

Problem: You find yourself in a situation where your attention isn't being pulled.

Why do phones pop out on the elevator? You don't need to check your notifications and do the whole ‘unlock, swipe, swipe, <yup nothing here just like I thought>, lock, put phone back in pocket’ thing just because there is a moment of no distractions.

Maybe the solution to that itch is fewer distractions in life, not more.

Moments of boredom don't need anything added to them.

V

Problem: I’m unhappy, and an advertisement told me this thing would make me happy.

Sometimes people buy things to fill a void. Sometimes, that void is even placed by the one selling the product. This doesn’t necessarily have to play into the ‘humans have a bias to add’ phenomenon. Regardless, there is a tendency to accumulate clutter and excess.

The committee's behind the DSM have not made being a minimalist a formal diagnosis. When they do (I say in only partial jest), I'll probably meet the criteria for Minimalist, moderate severity, with philosophical features. Over time, I’ve just concluded that having more things doesn’t solve problems; it just makes more of them. Having 20 bowls in your kitchen doesn't bring joy. Instead, it lays the groundwork for a giant pile of dishes sitting out for too many days.

I think the Pareto principle applies here. 80% of the contentment/practicality you get from the objects in your life comes from 20% of the objects. Most of your stuff is excess.

Buying <that-new-thing> won’t make you happy, but reducing the number of things in your life might.

There are other use cases. Many are small and not particularly worth writing about. Like noticing how this bias impacts the way I put up dishes. Inversion is a related mental model in which you start with a goal, figure out what would block that goal, and then invest your energy in avoiding your blockers of that goal instead of focusing on achieving it. As billionaire Charlie Munger says, “Be consistently not stupid instead of trying to be very intelligent.” Like inversion, just recognizing the bias of addition and having it in your ‘How to Life’ repertoire is enough.

Sadly, it took me a Nature Communications paper to appreciate that.

The tendency to prescribe has multiple causes beyond the bias toward addition. It also reflects flaws in the larger Healthcare system related to insurance reimbursement structures, lack of providers, pharma influence, etc. Still, none of that frees prescribers of their responsibility.

Reminder: Taking medical advice from people who say they are doctors online is a bad idea.

"Invert, always invert."

-Jacobi

"Don't be a dummy."

-Charlie Munger