Psychotropic Medications: A lesson on how to confuse patients

I

I have plenty of gripes with the mental healthcare field including (but not limited to) the tendency towards biological reductionism (reducing behavior to cells, chemicals, and brain structure), variable training in the conceptual competency, nosology (what counts as 'disease'), reimbursement structures, DSM-V overutilization, FDA approval process, over-reliance on medication, and more. Given all the frustrations built into the system and the existential nature of the suffering that comes from psychiatric troubles, it's no surprise that an 'antipsychiatry' movement exists. When the current mental health care system fails someone, it cuts deep. Mistrust is natural. Because of this, I often scroll through the antipsychiatry subreddit to see the various perceptions of the mental health field. Recently, this popped up.

If I had a mistrust of the mental health system to start with, I too would be wondering why antipsychotics are 'pushed on so many people without psychosis'. What kind of doctor would prescribe antipsychotics to someone without psychosis? I mean - Come on.

Something's afloat here, but it's not a conspiracy; it's bad communication.

Poor communication like this permeates a lot of the mental health field. For example, consider the term depression. Our hands are tied behind our backs as a culture when we use the same term for 'feeling down' as we do for the clinical entity that drives a person to end their life. This clinical entity, also called Big D Depression (note the capitalization) or Major Depressive Disorder, is a different monster than little d depression1. When asked to describe what Depression felt like, Tim Ferris who struggled with Depression for years said the following:

"It's feeling as hopeless and helpless as humanly imaginable while simultaneously realizing that your life is objectively quite good... there is a sense that you cannot escape the endless loops of your own mind."

An endless, pervasive mental anguish is different than a crappy mood, but our language doesn't always depict this well. Changes in sleep architecture, psychomotor retardation, etc. point toward some sort of biological basis2. Without awareness of this failure of language, the label 'depression' carries a lot of stigma and confusion with it. After all, can't they just get over it?

Psychotropic medications (i.e. medications that alter perception, mood, consciousness, and behavior) also have a communication problem and it causes questions like that found in the opening Reddit remark. So let's shine some light on the confusion surrounding psychotropic medications.

To start - an analogy.

Imagine a shiny metal fork, but its slots are filled in so it's a nonporous surface. Then, bend the edges of that flat surface up a little as to create a small bowl of sorts. It should look like this.

You may be unfamiliar with this ancient culinary utensil - it's called a soup-eater. It's been used for centuries to transport soup from people’s bowls to people's mouths. Remnants of these soup-eaters that date back to 1,000 BC have been found in the ruins of ancient Egypt. Intriguing!

But get this, somewhere along the way people realized that the soup-eater could be used to transport other foods. For example, we have sound evidence of it being able to transport applesauce, yogurt, and (as of last night with direct observational evidence) even fried rice.

Don’t be ridiculous - that is a soup-eater. A soup. eater. You must have no idea what you're doing if you're using it to eat yogurt. What's a soup-eater got to do with yogurt?

II

Okay - a bit silly, but this encapsulates the confusion around the varying indications of psychotropic medications. Such as why antidepressants are used to alleviate neuropathic pain, antipsychotics to help with Tourette's syndrome, and anticonvulsants (ie anti-seizure medications) in the treatment of Bipolar disorder. The name of the drug class is misleading. When you first discover a class of drugs, it's natural to name it based on what it treats. For example, antihypertensives treat high blood pressure. But doing so sets us up for confusion when it's discovered that the class of drugs can do more than that one thing. 3

This is what happened in our analogy. Soup-eater turned out to be a poorly chosen name considering everything else it can do. And we aren't pushing the limits of the soup-eater by trying to use it as a hammer or something. It actually is good at transporting yogurt. So perhaps we should rename the soup-eater from our analogy. Maybe a better name is 'food shovel', 'concave food transporter', or (though less fun) 'Spoon'. Then, it'd be less confusing when restaurants give you one with your ice cream.

This is analogous to what's going on with many psychopharmacologic drugs. Their original classification was logical, but later proved to not paint a full picture of the drug's capabilities. In many cases, the original classification doesn’t even paint a good picture, let alone a full picture.

Let's give a specific example - antipsychotics.

Antipsychotics do their 'antipsychotic' magic mainly* by blocking receptors in your brain cells that normally bind a chemical called dopamine. Therefore, antipsychotics are also called 'Dopamine antagonists' in the scientific literature. They antagonize (aka block) dopamine. But this name doesn't really mean much to most of the population who doesn't have a background in biochemistry, so the label antipsychotic gets used instead. In some ways, this is helpful. You don't need a background in neuroscience to understand what the pill is supposed to do and how it might help you. However, it's understandable - and not surprising - that simplification like this is inherently misleading. After all, if I'm not psychotic, why would I take an antipsychotic?Maybe if history had stuck with the term 'dopamine antagonists', there'd be less confusion as to why they are being used in people who are not psychotic. Everyone has dopamine in their brain - it makes sense that this class of drugs could impact, and potentially benefit, a wide range of people and not just those with psychosis.

III

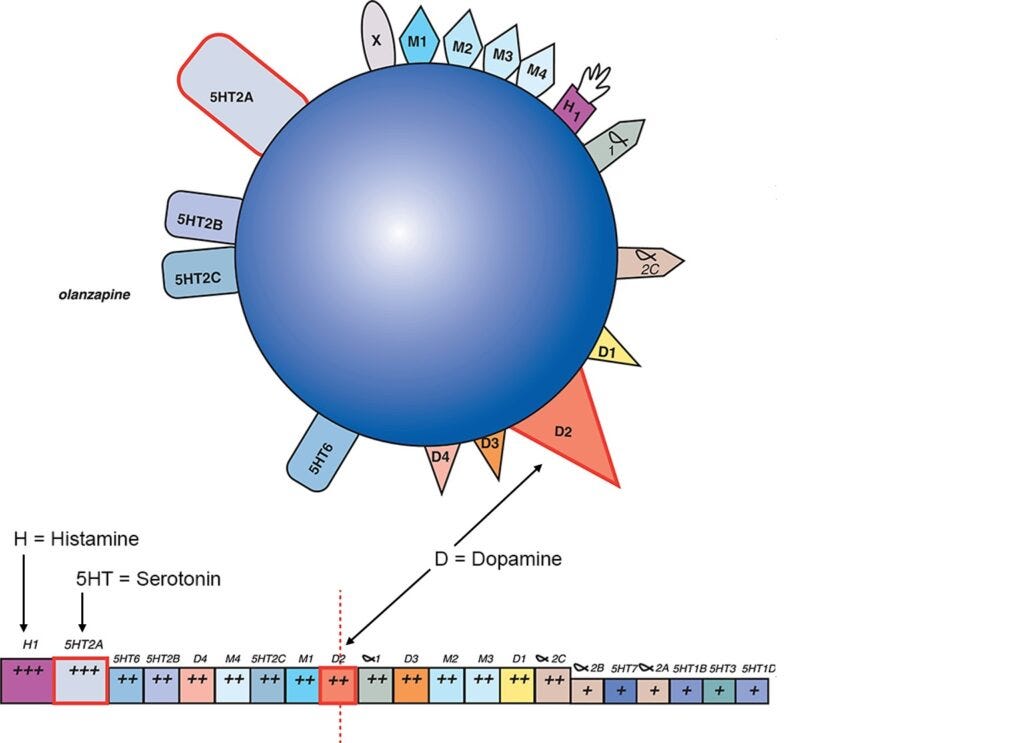

So far, I've kept it simple. But psychopharmacology is complex in reality. Below is a cartoon depiction of Olanzapine - a commonly prescribed antipsychotic/dopamine antagonist. You can think of each shape on the edge of the circle as a different arm that can bind to different receptors in your body. So from this image, you can see Olanzapine binds to a whole lot of receptors other than the dopamine ones we use it for. You can see at the bottom left, it binds to histamine and serotonin receptors better than the dopamine ones!

Maybe we shouldn't call Olanzapine an antipsychotic or a dopamine antagonist. Maybe we should call it an anti-histamine like benadryl? Or even better, let's call it a H1-5HT2A-5HT6-5HT2B-D4-M4.......5HT1D antagonist. That seems more accurate! But wait - what if we had a similar drug that binds the same receptors but with different affinities (I.e. the boxes at the bottom of the image would be rearranged and different in size)? Now we need to include the receptor affinities in the name for clarification...

You can see that it's easy to go too far down the rabbit hole with this.

As a patient, I would be skeptical of many psychopharmacologic drugs because of their names. I don't want to take an anti-depressant, Duloxetine, for my Fibromyalgia pain. Is this the doctor's way of labeling me as depressed? Why am I being prescribed an antipsychotic, Olanzapine, because I struggle with body image and have Anorexia Nervosa? Does the doctor just think I'm 'crazy'?

Perhaps a change in vernacular is in order. Maybe calling Olanzapine - that dopamine antagonist from earlier - a dopamine antagonist is better than calling it an antipsychotic. Maybe that will help prevent the confusion and distrust that our Redditor friend, /uThrowaway72718272 had. I don't know. But surely, calling Olanzapine an 'antipsychotic' is better than a 'H1-5HT2A-5HT6-5HT2B-D4-M4.......5HT1D antagonist'. And at the end of the day, maybe things should be kept simple for the large majority of people who come across these medications, don't have a background in biochemistry, and are prescribed them for psychotic symptoms. While imperfect, it’s possible simplifications like this are the best route to go. That's the goal of experts in any field - simplify things so that non-experts can understand what's going on. But, I don't know.

The mental health field faces a lot of challenging questions. It has a lot of ways to improve. But the point is that there is no sinister plot here where doctors and the field of medicine are blindly 'pushing antipsychotics' for the hell of it. The reality is a lot less conspiratorial - we're just doing a bad job communicating.4

Already, we can get lost in the weeds of definitions and labels.

All mental health conditions can be reduced to biological basis and neural chemistry. At the end of the day, it is all electrochemical. The more interesting question is what level of analysis (biochemical, psychological, societal, etc.) is best at capturing said condition.

This is done outside the mental health field too. Famous Viagra (a medication used to treat erectile dysfunction) is also used to treat high blood pressure in the lungs

I stand by this claim of bad communication. However, pharma influence is an issue too. Believe it or not, the world can be complicated.